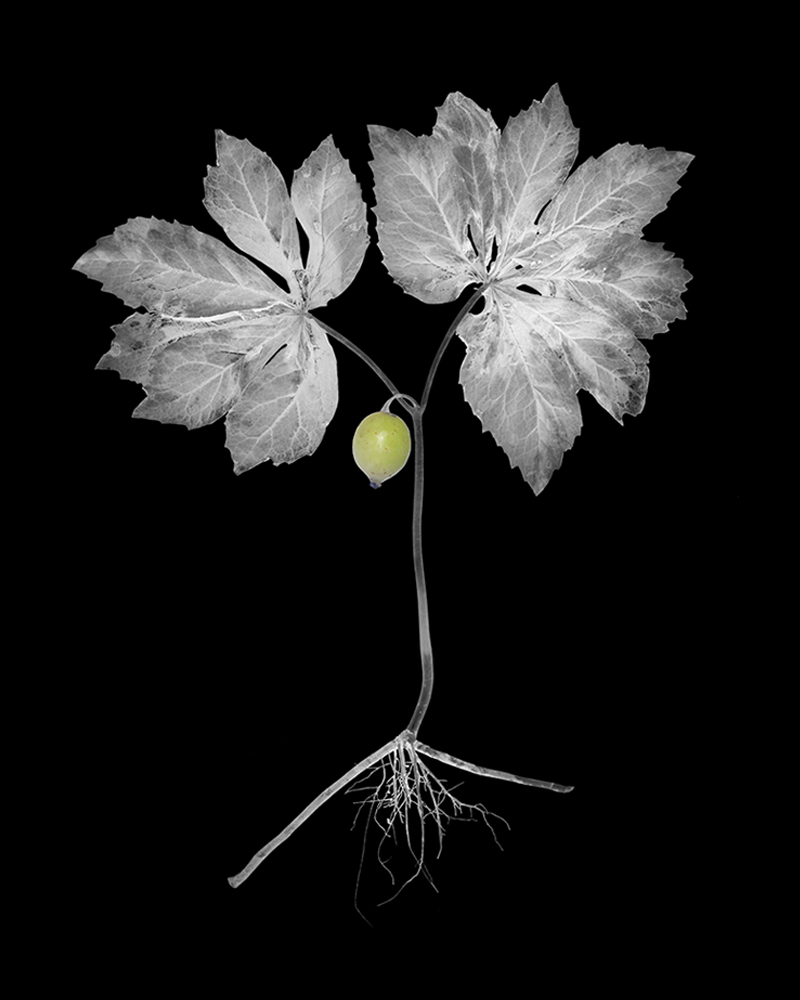

Zahra Reijs - Verse Vruchten

First and foremost, on behalf of the team at Broad, I would like to say that our hearts and prayers go out to everyone during this surreal time. We like to think of Broad as a global, family-like community, and hope that we can all come together during this time to process and overcome the uncertainty and fear surrounding this pandemic.

With love, Alexa Fahlman

As COVID-19 continues to spread rapidly across the world, life as we know it feels increasingly static. Restaurants, shops, bars, museums and libraries are closing their doors. Universities and public school systems are suspending classes. As our community spaces have shut down, and social distancing has become essential, it’s natural that we have all felt a sense of loss, loneliness and isolation. However, while we rest in self-isolation, I hope that this week’s series will remind us of the power of community–a picture of hope to look towards the life we will eventually return to once this is finally over. While we may not be able to gather in groups, meet for coffee or roam around markets, our communities remain just a FaceTime, text message, or email away.

Community is at the heart of Zahra Reijs’ photo series this week. “Verse Vruchten”, which is Dutch for fresh fruits, refers to the Blaak markt where Zahra shot her portraits of market-goers. East of Markthal (a modern foodie utopia), is the cheaper Blaak market: a huge open-air street market that sells all manner of fine foods to kitschy odds and ends. This market is a hub of culture, connection and community. Living close to this market in Rotterdam, Zahra remarks that she has always been amazed by the different styles and makeup she sees, so much so that she was inspired to compile this series.

Many of us have been to a street, open-air, covered, farmers, flea, or night market– or have at least seen one. Every culture has them; The souks of Marrakech, Tsukiji Fish Market, Marché aux Puces de Saint-Ouen, Grand Bazaar, and Portobello. In spite of their regional particularities and differing spatial forms, these markets have a ubiquitous universality- public spaces of inclusiveness and heterogeneity. Markets are accessed by and accessible to everyone- they function as a public space which is both economically and socially inclusive. As such, markets are often the most socially diverse public places in communities, bringing together different ages, genders, ethnicities, and people of varying socioeconomic statuses. Here, people–especially marginalized groups–gather over the experience of food, shopping, and conversation. These are spaces in which we can freely loiter, mingle and become accustomed to each others’ differences in a truly everyday, public and improvisational space. With community spaces such as markets, which inspire social inclusion and the mingling of different cultures, we are able to grow our sense of local community based on connection, interconnection, and social interaction.

Do you think the culture surrounding the Blaak markt is threatened by the city's globalization, especially with the big Markthal Hall? Or do you think that the big hall has brought more tourism to the Blaak markt and has helped support the vendors?

Markthal is super expensive and commercial compared to the local market so not many locals go there for their groceries. Also, Rotterdam locals are quite stubborn and not very easily impressed by new big concepts like Markthal, so I guess that helps haha. The city has gotten much more busy in the last couple of years, so in the end, a lot of businesses including the Blaak markt improved their sales and become more popular.

So, do you hope that the city will preserve the Blaak markt as a social space?

Definitely... its not just about food but it’s a social gathering as well.

When you first submitted your photos, you pointed out that your series was dominated by female portraits. Was this a conscious decision?

I’ve always been more interested in photographing women. I can't really put a finger on why, but I feel like it has something to do with projecting a part of myself onto my portraits. It makes the most sense that I would project this onto women since I am one myself!

I’m also mesmerized by the movement of women. There’s beauty, even if it's just within a flicker of their eyes. Perhaps, as a woman, we just simply have a different connection to women than with men…

“Photography is the best excuse to get yourself into someone else's world and out of your own–that is something I'll always cherish.”

Why do you think there is such a concentration of unique characters and playful dressers at this particular market?

Rotterdam, with over 170 different nationalities, is the most multicultural city in the Netherlands! If you walk around Blaak market there is such a beautiful mix of cultures to be seen, which translates to the way people dress. I don't think they realize their sense of playful fashion/self expression as you call it; it's just the way they are...it's as pure as can be.

What was your favourite part about shooting these women?

People in Holland are pretty closed off and like to live in privacy. Some days, I can’t find anyone who wants to be photographed. Yet, those who do show themselves proudly, some still aren’t sure of how to react, but I really hope they realise how beautiful they are.

Personally, I love markets! I think if we had more of them, society would be more colourful and accepting. Do you think markets are a way for people to re-learn community in a world which is constantly becoming more removed?

I agree! It’s becoming a rare social gathering where–for once–it doesn’t matter where you’re from, what you do or who you are. To me it also feels a bit like film photography, or writing a letter instead of a text message. I guess you could say that this way of “market-living and connecting” is more authentic than the main world we live in right now.