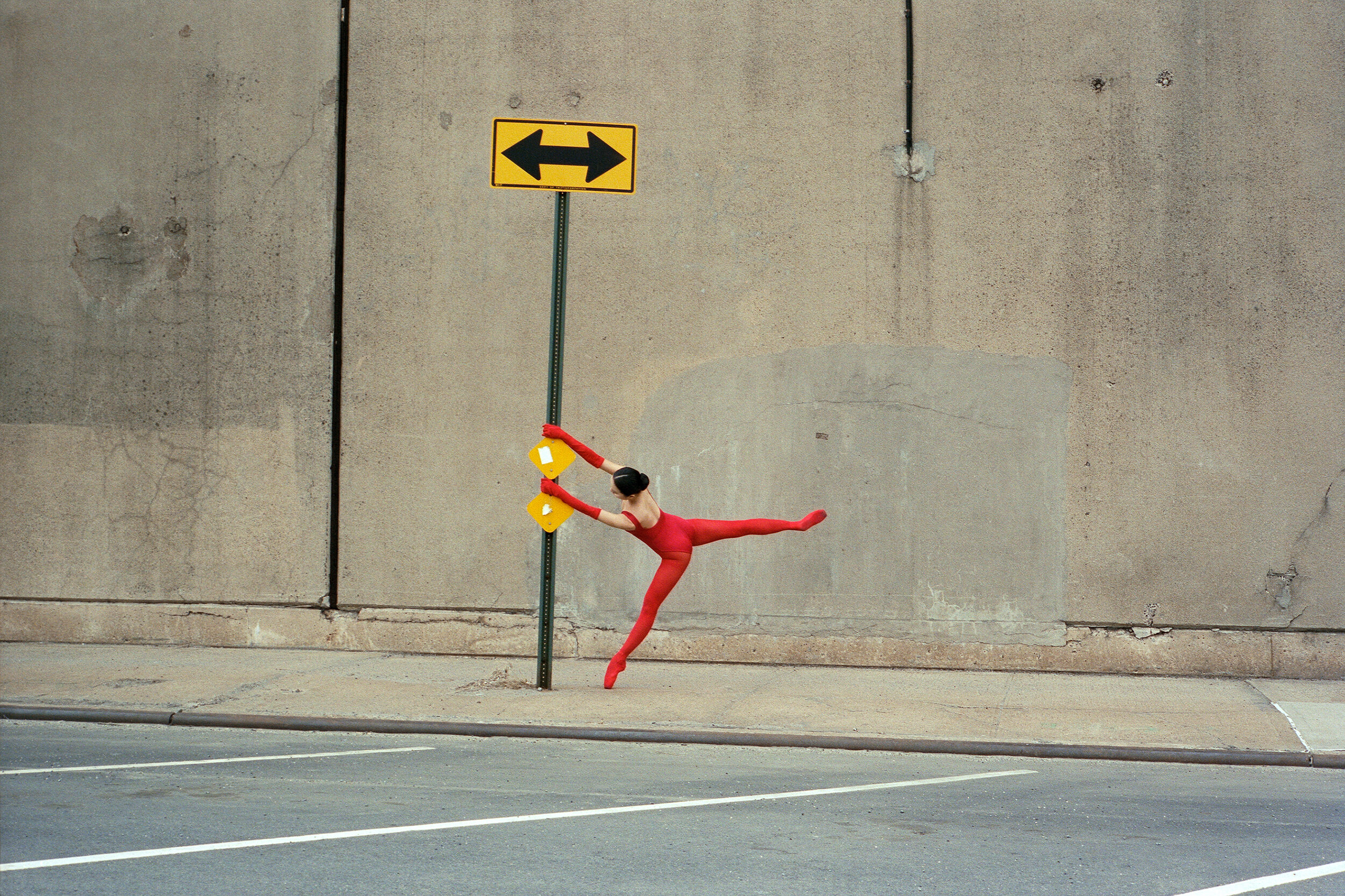

Ruby Steele- Women on Sofas

With Mother’s day fast approaching this Sunday, we’re starting off this week by celebrating Ruby Steele’s “Women on Sofas”. Ruby’s series challenges the Western traditions of domesticity and womanhood, exemplifying how “woman” and “the domestic” are not mutually exclusive terms designed to limit one another. Rather, the women in our lives are not only mothers, but are–”daughters, friends, strangers, writers, artists, models, priests, students, business women, entrepreneurs, musicians, actors, doctors, scientists, technicians”– and anything they choose to be.

- Alexa Fahlman

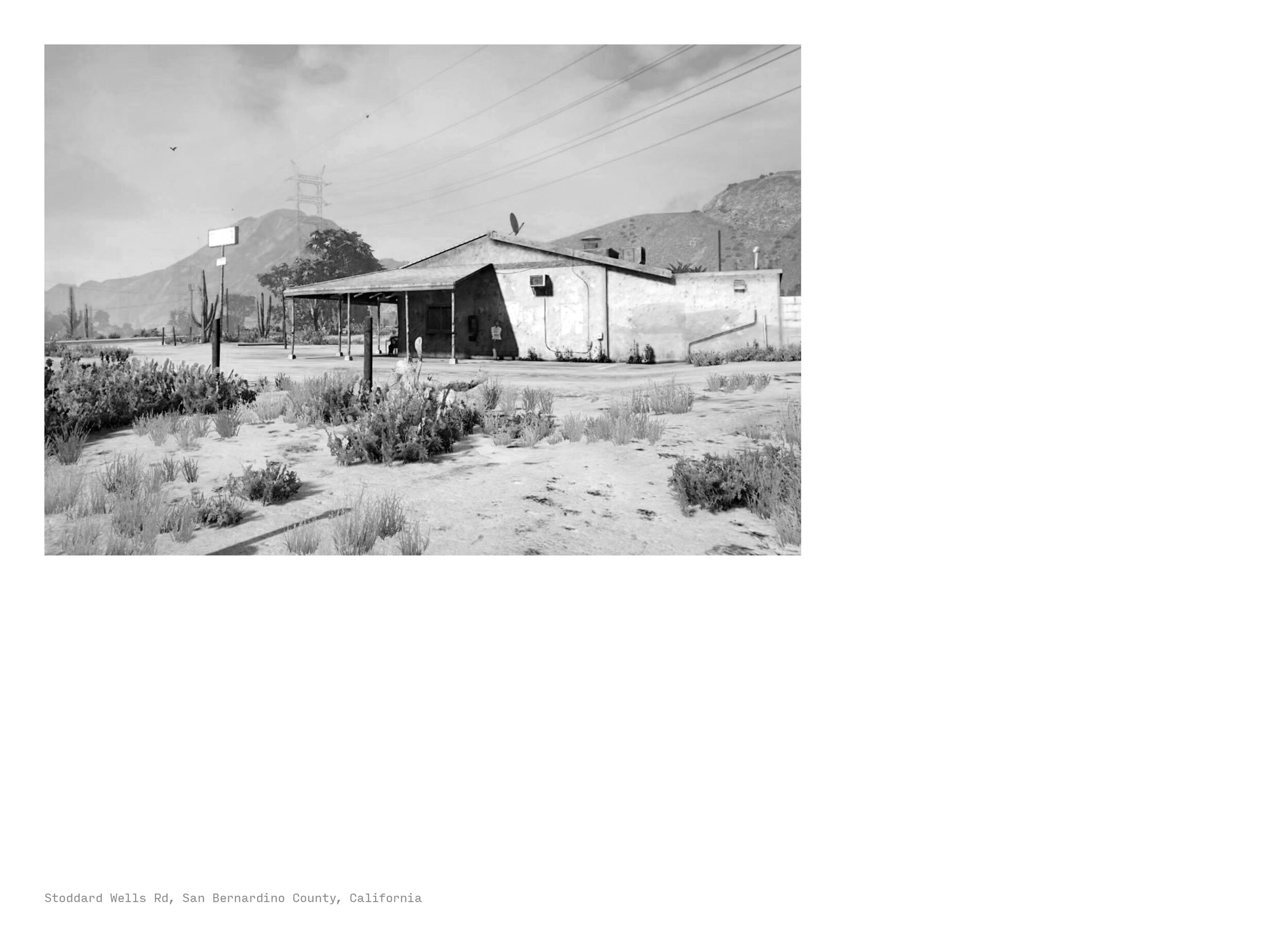

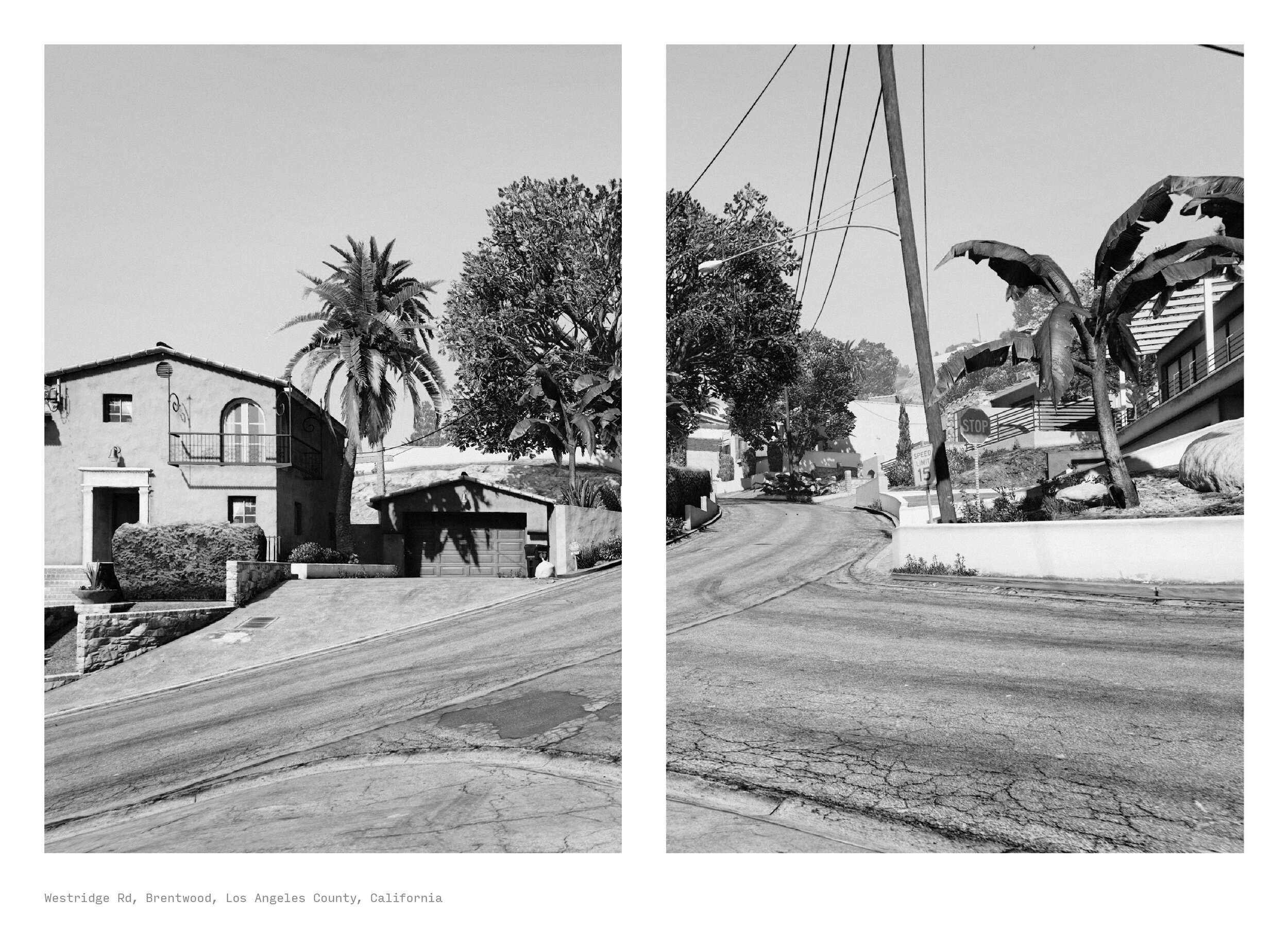

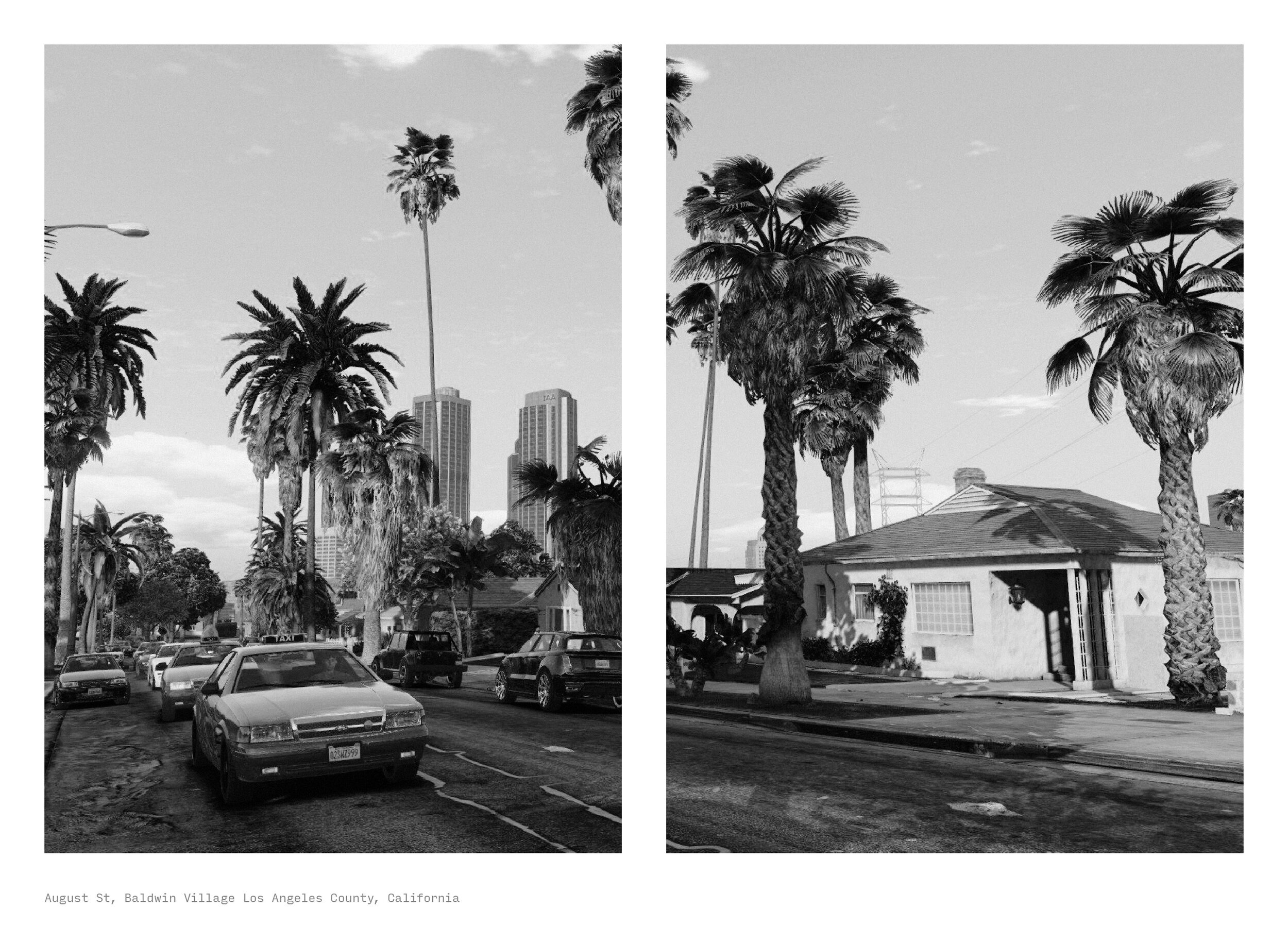

The domestic space is one we all understand. A home, no matter which way you view the word, involves spaces of conversation, activity and thought. Such spaces hold the potential for negativity and positivity. It is interesting to observe how a space holds itself for someone, and their emotional response to it. Feminist critique considers the human geography of space, both in the gendered nature of space and existing conceptualisations of space. A magnitude of diverse environments within our society differ in their pre- existing tendencies to welcome one gender or the other. Culturally, we are encouraged to adhere to this. “Women on Sofas” was driven by a curiosity about the space a woman occupies in contemporary western society. The work explores how we experience ourselves in the domestic and public arenas, whilst celebrating our diversity and power in unexpected ways. It looks at the pride and pleasure we take in our strength and resilience, and in challenging society’s expectations of us. In spite of growing freedoms in many areas of society over the past century, the domestic sphere is still often seen as women’s terrain. It is a space into which we are welcomed. It has been interesting to observe this space, disrupt it and take it beyond its ‘natural’ limits, whilst exploring our emotional response to it. The women come from diverse backgrounds and cultures which span eight decades. They are mothers, daughters, friends, strangers, writers, artists, models, priests, students, business women, entrepreneurs, musicians, actors, doctors, scientists and technicians. Women on Sofas was the project that offered me the opportunity to celebrate these women, both ones I knew and ones I was yet to meet. The sofa is more than a domestic object; it is imbued with symbolism and a rich history. It holds a familiarity and is an invitation for togetherness. These photographs bring that intimate space into the outside world and ask us to reconsider what it means to get comfortable, and feel safe. They also consider the social function of the sofa, and allow that function to broaden into the idea of bodily experience. The image of the sofa initially suggests inactivity. “Women on Sofas” works to challenge that. “Women on Sofas” says ‘I am in the world, I’ve made a surprising home here, and now I’d like to welcome you in.’