JH: When creating your MA project “Vorest” what was it that inspired you to make the work? You, like myself, have a lived experience of the landscape you based the project in, but what other elements drove you to look deeper into it? And did you become further invested in that personal connection as the project went on?

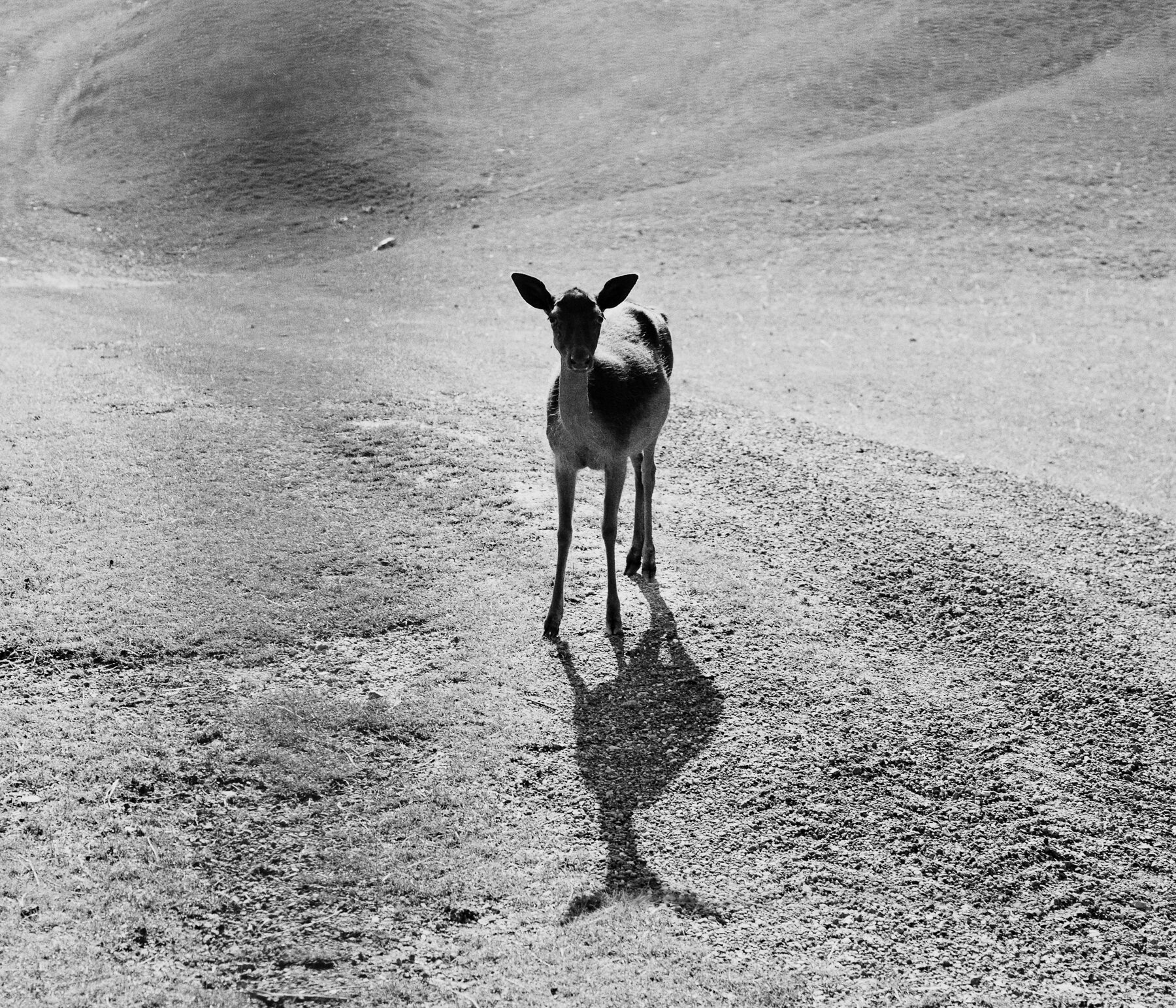

PK: For years I have been intrigued by the landscape of the Forest of Dean and its rich culture of land use. Its woodlands have a mysterious allure and the ancient land-based rites that are still upheld today are particularly unusual. The one I have always found most fascinating is the rite for “Foresters” born within the historic boundary to train for a year and a day (or more) to become a Free Miner and open their own mine of coal or iron ore. It is traditions like this that form the foundation of the Foresters’ culture and collective memory.

I had made work in this Forest twice before. They were long term projects during my most formative years as a photographer. I still felt a need to continue photographing there, to walk in the woods and the common land I had not yet discovered, and to dig deeper into the cultural history of the Foresters. I grew up on the outer edge of the border to this Forest that I have always wanted to call home, but never quite belonged. I am in some ways a Forester and an outsider, able to move between the two. The personal connection I have with this place has grown immensely with the development of this project. The two are so intertwined, that I can no longer be sure where one begins and the other ends.

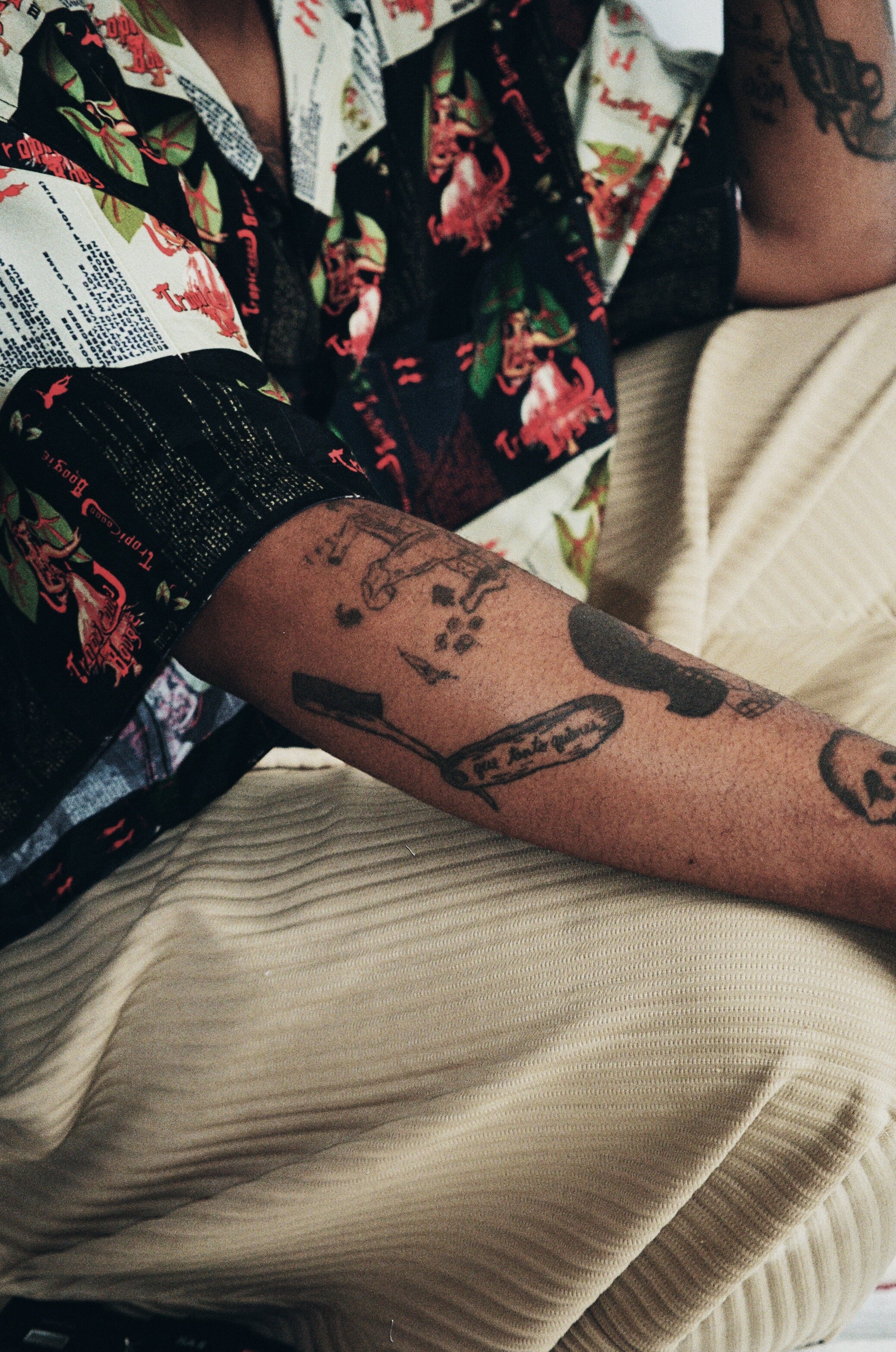

JH: It took me some time to find an isolated portrait within the work, the relationship between the people in your images and the landscape is enveloping. There is a sense of entwining between the two parties which is presented in your photographs. Was there an intention to develop the tactile nature of the landscape toward the viewer?

PK: Absolutely. Landscapes are material. They are something we dwell in, act in, think in. The material elements of landscapes create different experiences for us. Here, for example, there is a particular feeling of being surrounded on all sides when you are far from the threshold to an old woodland, and straying from the beaten path. Or, in the heathland, where the gorse is sharp and rough, and the ground is soft beneath your feet. You choose the clearest path, and probably regret wearing shorts. All of these elements are material and tactile. I have tried to capture them in detail and in expansive panoramas that place you within the landscape.

JH: Having spent such a long time with the “foresters” who inhabit this environment and researching its ecology, what are your thoughts on its role within a modern society? For example, does the work fall within the issues facing climate change?

PK: This work does contribute to those wider discussions on climate change. The term “climate change” is vast and often daunting (and rightly so, it is terrifying). I believe the urgency doesn’t always reach people on a personal level. Which I think is necessary to really promote change.

In this Forest, there is a collective desire among the inhabitants to maintain the ecological balance of their land. It is the foundation of their culture and collective memory. Recently, there has been a shift towards promoting activities and education within the local environment. There has also been a vast project to restore heathland and wetland, which is still ongoing. Large areas of this Forest, the common land and nature reserves, are open to be freely explored.

I do see the way this place is managed and inhabited as an example of what is possible when a community promotes education and conservation. When we really experience our natural surroundings in our everyday lives and form lasting memories, we are more likely to develop a life-long relationship with our environment, and to care more deeply about its well-being.

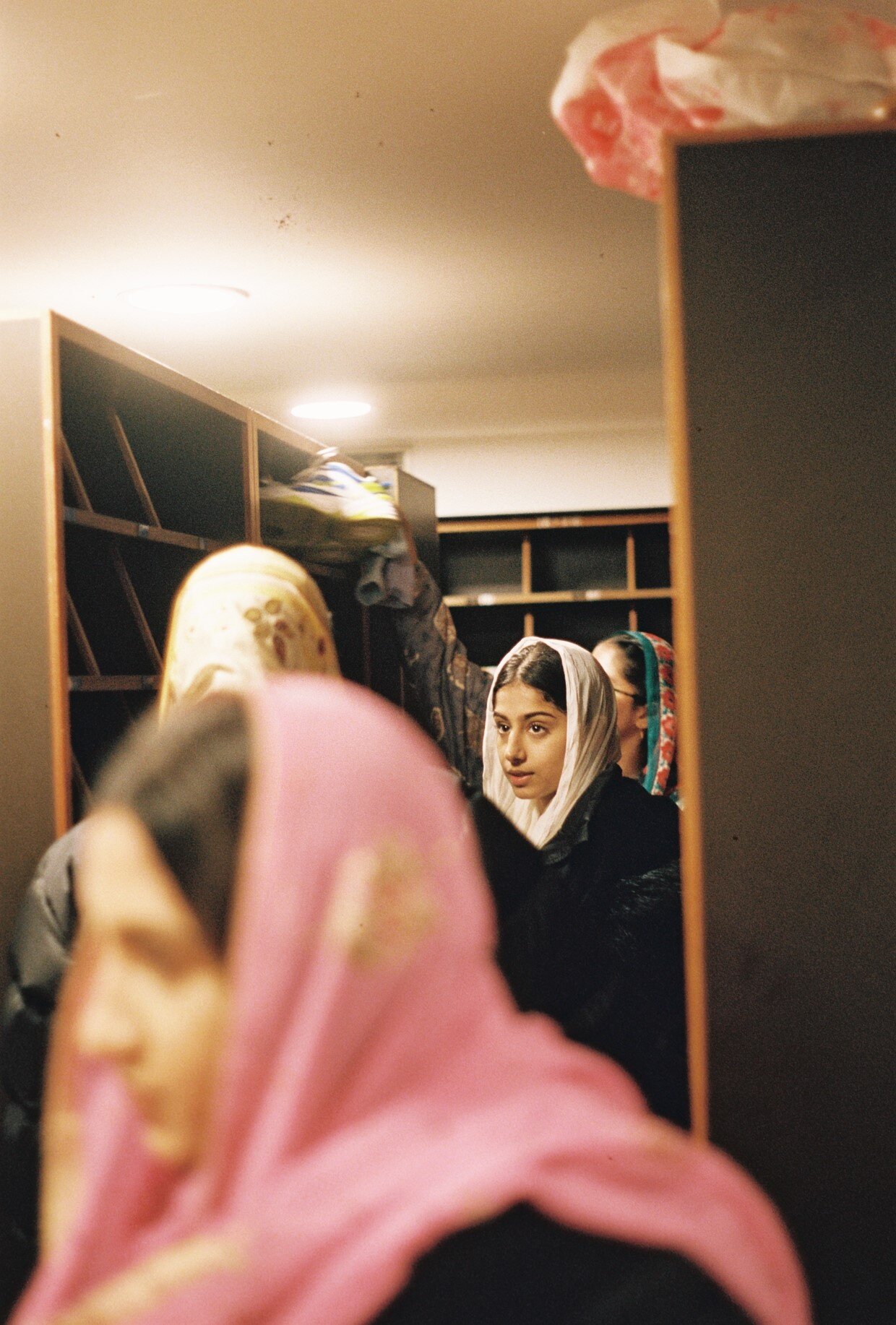

JH: WIth a lot of British history and folk tradition there is often an element of spirituality connected to it, whether that be religious or more individual. The landscape in your images evokes the corporeal component of this, do you see the landscape in your work as one of the same as its inhabitants? What role does spirituality play in the work?

PK: The landscape of the Forest of Dean is certainly rich in folk tradition. In my research, I read many of the local stories, some very real and others more fictional. I mapped the sites of historical significance, with their picturesque names. Titles which often alluded to the subject of the folktales that surround them, and sustain their mysterious allure. Photographing these places corrupted the aura that their names and associated tales created. They were disappointing and banal. It was on the solitary journeys to these sites, and in the other places I sought for their topography, that I found that aura of spirituality or myth.

The Foresters and the landscapes they inhabit in this work are certainly very closely connected. The archive photographs I selected from the local museum’s collection show the actions of the land and how it used to be managed. My own photographs show the landscape as tactile and material. A place in which the human role is reduce, but still present. Together, they form a visual dialogue that considers the narratives of the past with the environment in the present.

Throughout this project, I was very conscious of the connotations of the rural idyll and a desire to actively avoid such idealism in the narratives I created. Which brings me to my first question. In your own going project “Terrain Vague”, how have the visual and literary ideas of a traditional and pastoral Britain featured in your work and your research?

JH: The division between urban and rural perspectives and the mythology of the countryside played a big role in the making of this work and really served as a way to contextualise it. Like a lot of myths, there is often some truth to them and with the British countryside that is also the case, it is idyllic and it is tranquil. However for me, what makes a story interesting is using those associations to help counter the argument and tread that fine line between the myth and reality and this was a balance. I really tried to strike. In order to do so I made myself very aware of the culture that has transfigured our real landscapes whether that be movements in painting such as the Romantics and Naturalism or their literary counterparts like Keats or William Blake. So as to be able to acknowledge them and use this iconography to guide a new narrative without getting too close to nostalgia. I chose to photography all along the road in question as I wanted to pull in sciences which are normally connected with this real tranquility into scenes more associated with industrial decline. These pastoral scenes associated with romance and aristocracy are so strong that contrasted against more “urbanised” scenes, I hoped to cause a tension which could run throughout the work and allow for questions to arise.

PK: Some of your landscapes seem to reflect the style usually associated with the banal American landscapes of the New Topographics. The British and American landscapes are two very different places; historically, culturally, and topographically. How have you been influenced by the real and suburban landscapes of other countries? Has looking outside of British photography helped you to subvert those stereotypical ideas of the rural idyll?

JH: In my opinion, what Americans are very good at is using photography as a critical lens and playing with its transformative abilities. I have a real fascination with the evolution of photography in America because it is so intertwined with their history, each step of American idealism has been witnessed by photography. This may be why they have such a deep connection to the medium as a critically descriptive tool, however that is not to say that we do not. But when looking to break away from the rigidity that can be found in photography, the contemporary American practitioners for me, are a very good place to start looking. When I was thinking about how to confront the stereotypes of the rural idyll it was a real awakening to look at how the American photographers were using their real narrative of “The West”, as they were able to bring vernacular life to a position of power from which individual lives and narratives could be used to discuss the inequalities of their nation. Generating that power within a subject by not describing an accurate photographic depiction but elevating that person or object from banality as you put it. It is an evolution in the concept of “photographic truth”, how do you truthfully document a landscape in a medium which is founded in aesthetics? Anyway, it is getting to phenomenological, the transformation from the everyday to metaphor is where documentary is beginning to sit comfortably and is where photography has its power to me. When looking at our landscape, this lived and known space, I wanted to achieve a similar goal hat the photographs of The West do, in that I wanted the iconography and the reality to communicate.

PK: As you mentioned in your first question to me, we both have a lived experience of the landscapes we based our projects in, so I would like to ask you the same question. What was it that inspired you to make the work? What other elements drove you to look deeper into it? And did you become further invested in that personal connection as the project went on?

JH: What I was trying to accomplish at the start of making this project was to help form an updated perspective on what it meant to live in a rural area in the UK. Having spent a lot of time travelling along the road and having grown up on the east end of it, I felt I had a ground view perspective on the nuances that could be found. While working in London, the interest grew as I came across peoples’ interpretations of the countryside, often very idealized and surreal. It didn’t fit with the depth that I had seen in such areas and to an extent, it frustrated me. I was always reminded of the film “Withnail and I”, I’m not sure if you’ve seen it, but it’s such a brilliant representation of the urban/rural divide within pop culture. When I began the work, I really didn’t know how to contextualise it and how exactly I was going to communicate the complexity and diversity. As the project went on, I began to be able to formulate and understand the work a lot better which drove the interest in the project further. I am now more than every really fascinated by how we categorize and build our sense of place via the culture and sociology found within it.

PK: The complexity of real life is often overlooked. The stretch of road you travel in “Terrain Vague” is an example of the ever changing British landscape. The landscapes you have photographed are often the in-between places, the ones deemed of little value to development. What do you believe gives these spaces significance? And do they have a place in the formation of local identity?

JH: I have a bit of a love hate relationship with “labels” which makes me sound like an angsty teenager, but the problem I have with very defined aresas, or understood landscapes, is that they are just quite boring. They are also really hard to reimagine and because of that my eye tends to wander much more towards the spaces which are hard to categorize. When you look at areas which form on the edge of these constructed or known spaces you find a lot more conflict and interaction between opposing elements and that really interested me. It took a long time to find a way to understand these areas and during my research I came across a couple of books which really helped me put it into words; The Anthropology of Landscape by Christopher Tilly and Kate Cameron-Daum and Non Places by Marc Augé. Both of these texts brought my thoughts to a more structured place and actually generated more confidence around the project. I’d like to add a little quote which presents the thinking behind a lot of my photographs.