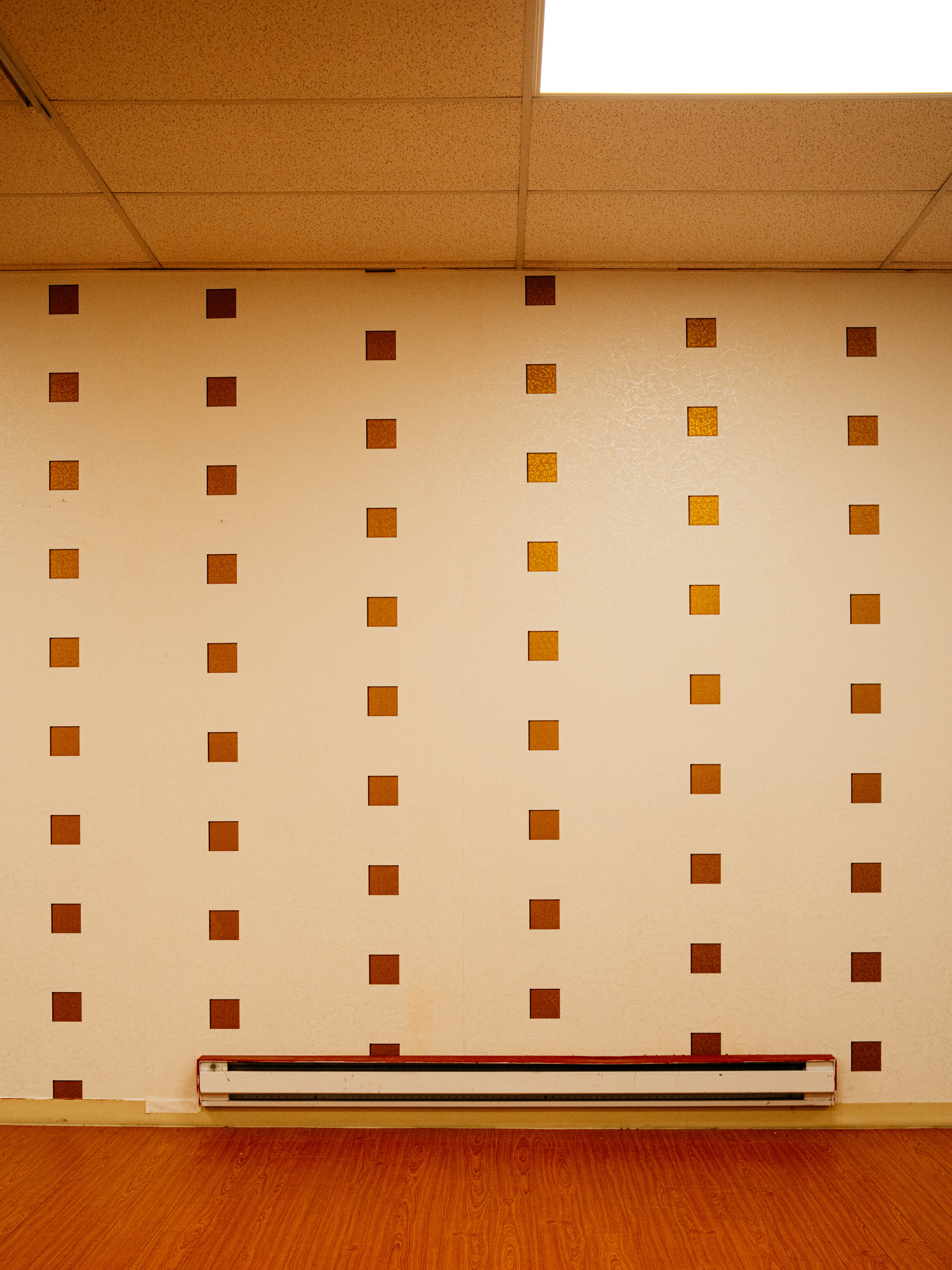

Chad Wong - Empty Spaces That Fill My Heart

While Chad Wong began Empty Spaces as a simple exercise to further explore the compositional aspects of photography, his project soon became layered with personal meaning. In turn, Wong’s initial focus on shadow and light functions to highlight the lingering effects aesthetics have on our associative cultural memory. In particular, he muses on the role Chinese-Canadian plazas play in East Asian diasporic identities, noticing how an patterned carpet, or green-chaired food court can trigger a collective, and cultural nostalgia. Here, we talk with Chad about the relationship between space and cultural identity, and how, despite a seeming emptiness, these spaces can still fill our hearts. Continue below for the full interview!

- Alexa Fahlman

What role would you say these Chinese-Canadian malls play in East Asian diasporic identities? Especially within Vancouver's cultural context?

C: In a practical sense I think it offers a space for alternative businesses that can only exist exclusively within the Chinese cultural context, think Chinese medicine apothecaries, classrooms for tutoring, a place that sells pirated DVDs and sometimes even a live fish market. But, at its core, I find that these spaces seek to provide comfort and familiarity to those who have immigrated here from Hong Kong and China. This of course can be seen through the architecture of these spaces. In many ways, Vancouver has a very distinct Chinese-diasporic culture in that it is spread out and sprawling across the city. To me it often feels as if there are two Chinatowns. In Richmond you will encounter Chinese-Canadian malls that are more influenced by the aesthetics seen in the late 90’s and early 2000’s architecture of Hong Kong. But as you travel towards Chinatown and East-Van you start to see places that are generally more influenced by an older generation of immigrants dating back to the goldrush. With that being said, you would be hard pressed to see anything remotely of semblance if you travel to Hong Kong now. It is as if through time it has evolved and created its own specific visual language that entirely belongs to Chinese-Canadian malls.

With that being said, on a more personal note, I believe that these malls play an integral role as a space that acts as a cultural connector between first and second generation Chinese-Canadians. Experiences that may seem abstract to my generation from the stories our parents tell us can be experienced in these places.

You mention on your website about bringing attention to the cultural cohabitation and the growing chasm between the English-speaking and the Chinese-speaking communities within Richmond. Could you speak more on this?

C: In 2018 myself and another emerging artist Crystal Ho were given the opportunity to undergo an apprenticeship with Evan Lee, an established artist from Vancouver to work on a public art project in Richmond. The theme of the project was centered around migration, among the many discussions, we eventually honed in on two major factors which contribute to the migrant experience and that was food and language. For me, someone who grew up in both Candian and Chinese culture I always felt that there existed an in-between status among second generation immigrants. In the end, my project took the form of a text-based piece that is reminiscent of the many menus seen in Hong Kong style cafes. The menu, rather than a typical translation between Chinese (in this case Cantonese) and English is instead transliterated. As such, it required someone who understood both languages to decipher this menu or two people who could only speak one of the languages to work together. Ultimately the goal was to encourage dialogue and conversation between those who may not often get a chance to communicate. As mentioned previously, Richmond is a unique place in North America in that one does not need to know English to live or even thrive. That is not to say that it is particularly a bad thing but I believe that this creates a cultural enclave that inadvertently alienates those who cannot speak Chinese, shutting down dialogue and perpetuates negative stereotypes from both sides.

While this current project does not directly address these issues, I feel that Chinese-Canadian malls provide a decent gateway for those not of Chinese descent to be able to share in our culture and collective memories.

At what point did your project turn into a much more personal reflection of nostalgia?

C: While this project began as a simple exercise on understanding lighting and shapes, as I continued with this exercise I found that I was subconsciously drawn towards photographing these semi-abandoned malls. I think at the time (and still) it gave me a lot of comfort to document these places, as if I am preserving a part of my childhood and adolescence. But more importantly, I think it was when the protests in Hong Kong for democracy were in full swing. It was difficult not being able to participate in the front lines and I felt the only way that I could release these feelings was to photograph these places that reminded me of Hong Kong. In a way it more or less signaled a beginning to an end to my personal relationship with the city, I remember traveling back in 2016 and realized all the places I used to frequent are no longer recognizable and that I could never go back (physically since the passing of the National Security Act and spiritually as the city continues to evolve). As a result, these malls felt more like Hong Kong than Hong Kong does to me and it is in many ways romantic to me. But perhaps these spaces only resonated with me and I began to question why; it all seemed so arbitrary, would someone who has never been inside a Chinese-Canadian mall have the same feelings when looking at these photos? I think that was when I started to question the notion of nostalgia in photographs and art; is it possible to communicate these very specific feelings through my documentation of these spaces?

Conceptually speaking, what is it about the everyday and mundane that strike you?

C: I think it is because the mundane is so invisible yet so impactful. It is always hiding yet present. You can walk by a place a thousand times and not bat an eye. It is only when you revisit the same place and suddenly all the feelings you never knew that were associated with that space comes rushing up. In that sense I feel that the mundane attacks our subconscious in such a way that it shapes who we are.

Reflecting on a deeper note, racist assaults towards Asian communities have evidently increased in North America due to Covid-19. How do you cope with what feels like such constant bad news? Has this at all affected your photographic practice?

C: It is definitely deeply concerning, certainly Vancouver has a checkered past in regards to racial discrimination against the Asian communities. While I am lucky not have encountered these acts first hand, I cannot help but remember when SARS in 2003 was in full swing and the discrimination I felt as a child. In many ways, that experience has taught me to be more wary and in general just act more defensively, which in the era of Covid has its benefits. For me the best way to cope is just to spend more time with family (within your bubble of course) and photograph more. In a way, I think Covid has somewhat made this project easier to continue as most places are in fact quite ‘empty’ so in that sense, it has been a small sliver of light.

I do have to point out that as these tensions grow, the cultural chasm we discussed earlier will continue to widen. And we have to be careful as Chinese-Canadians to not fall into similar prejudices as the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) funded news outlets aim to weaponize theses acts of discrimination against the Chinse population in North America to drum up blind nationalism.

Tell us about your creative process. How do you go about making images, from start to finish?

C: Comparing this project to my previous ones I feel that this may be the most challenging, I do not often work with representation in my work, even when working with photographs it is with the intent of abstraction and dissection that I go about constructing those pieces. With that being said, I find myself starting with a memory of the place, whether it be going to buy groceries with my mom or hanging out with friends getting bubble tea, I try to bring myself back to that day and access that memory. I typically shoot around 50 images in one area but only end up picking around 10. Generally I just walk around and look for good lighting, sometimes even just sitting and waiting for good lighting. The editing process is where everything comes to life, if photographing is documentation then editing is painting. This is where, to me, all the emotions begin to imbue itself into the images and where I can tell the story that I set out to tell

Lastly, I'm half Chinese myself, and one of my fondest memories is going to the Crystal Mall Food Court with my gong-gong and mom. You capture such a unique nostalgia that I, and I'm sure many others, can only really associate with a Chinese mall food court. I'm curious to hear your thoughts; how is it that such "empty spaces" also tend to be the ones that fill our hearts?

C: To me ‘empty’ refers to not just the physicality of the space but also spiritually, while some of these malls are in fact rather desolate, others are still thriving, but they feel empty. I think these ‘empty spaces’ fill our hearts in the same way hot soup fills our souls during the dead of winter. It is familiar but comes with a twinge of melancholy that brings us back to our childhood. When we come back to these ‘empty spaces’ we are also confronted with our own personal progress; what have we lost and what have we gained along this journey and in a way I think that brings a lot of comfort. But the most enchanting thing about these spaces for me is the fact that they are not SO empty, they are not entirely abandoned spaces. In fact you can still see a small but dedicated few who frequent them, whether bound by proximity or by loyalty, and I cannot help but wonder: ‘what are these people holding onto that I have left behind...abandoned?’ Perhaps the attempt of discovering the answer is what ‘fills my heart’. In that sense, it reminds me of Wong Kar Wai’s titular film Chungking Express; what stories do the middle aged woman, the kid working on his math homework, the ah-yi working at the wonton stall have to tell and how similar are our experiences?