Tommy Sussex- Black Lives Matter, London, UK.

Photographer Tommy Sussex documents BLM’S global movement as it occurs in London, UK. These photographs were taken during two Black Lives Matter protests- Sunday 31st May 2020 and the 3rd of June 2020.

Photographer Tommy Sussex documents BLM’S global movement as it occurs in London, UK. These photographs were taken during two Black Lives Matter protests- Sunday 31st May 2020 and the 3rd of June 2020.

Ferris Bueller

Not bad words to live by from the sausage king of Chicago. It’s hard to keep this mantra in mind in today’s world but when I walk the streets of Anytown, USA invariably someone will try and bum a smoke from me. Camera at the ready I state ‘Of course you can have one, but i’ll need to take your photo’. I stop and look around. These photos are the result.

NYC Subway, New York City (2019) | Bar X Salt Lake City (2019)

Outside TAO, New York City (2019) | Lower Manhattan, New York City (2019)

Lower Manhattan New York City (2019) | 6th Street Plaza Los Angeles (2019)

Lower Manhattan New York City (2019) | Bar X Salt Lake City (2019) | Double Down Saloon New York City (2019)

Chevron, Austin (2019) | Short Stop, Los Angeles (2019)

Gold Diggers, Los Angeles (2019) | Little Joy, Los Angeles (2019) | Gold Diggers, Los Angeles (2019)

Yellow Jacket, Austin (2019)

6th Street, Austin (2019)

Gold Diggers, Los Angeles (2019)

Shangri-La, Austin (2019)

Johnny’s Los Angeles (2018) | Unknown Bar, Los Angeles (2018)

Ace Hotel, New York (2018) | Lower Manhattan, New York (2018) | Ace Hotel, New York (2018)

Downtown, Chicago (2018)

Wynwood, Miami (2018) | Lower Manhattan, New York (2018)

Wynwood, Miami (2018)

Hythloday is a body of work that draws from a community’s fight against fracking, and seeks to present their experiences and beliefs through a visual interpretation of what is positioned between fact and fiction. In the United Kingdom, the trial site for hydraulic fracture (shale gas fracking)–and its potential for national rollout and future commercial exploitation–is located in the countryside between the cities of Preston and Blackpool. A mile down the road from this site, a group of activists known to the local community as ‘The Protectors’, set up camp where they live and fight against this fracking trial.

In what might be described as a “photographic novella”, Hythloday transforms this physical place into an imagined post-fracking scenario, in which the activities, causes, fears, effects and thoughts constitute a potential future landscape. The project draws its title from a character’s name in Thomas More’s Utopia, and is used as a means to explore and understand the place itself, as well as ‘The Protectors’ fight. Hythloday combines the characters and elements on the ground with the suspended mood of an on-going protest to create a journey through an unknown and strange place; ultimately, revealing the tension between the subjects portrayed and the land they inhabit.

Continue below for the interview between Norberto Fernández Soriano and Alexa Fahlman

What inspired you to document this particular community's fight against fracking?

Initially I was interested in how this activity would modify the landscape and thus, the ways of living. I was also curious about showing the effects on the strained relationship between human and nature, especially in the rural areas where fracking is being tested. Since the effects manifest in the long term and can't be observed on the surface, I decided to explore the community’s fight against fracking, documenting their beliefs, fears and experiences.

Is this still an on-going fight?

The fight is still on-going, as the fracking is still on-going.

One of the most direct pieces of evidence that reveal the effects of this practice are the tremors which are felt in the surrounding areas. The monitoring system that should guarantee the so-called “safe” levels of fracking show that these have been surpassed on several occasions. Despite the different maneuvers to continue fracking, last December, all activity was finally halted on the site where the project Hythloday had been developed. Nevertheless the records confirm a real risk– trial sites for fracking keep on spreading across the country.

Is The Protectors' protest entirely for environmental reasons, or were the reasons also more varied, scattered, even?

The Protectors, as a group, is a cluster of environmental activists and people from local communities. The background of this group is very heterogenic, but fracking is what made them come together. Some of them are activists who have been involved in environmental issues their whole lives; some have long given up on today’s society; many were locals, directly affected by this activity; while others, disappointed with the reality they have had to face within their jobs, have decided to put their efforts into something more meaningful. Most of the local community would have never thought of themselves as protesters or environmental activists, they were leading a tranquil life in an environment free of threats to their lifestyle. When the fracking rumours started, people did a little bit of research and they soon realised that this was something they didn’t want happening near to their homes.

I think it is the communal sense of fight and resistance which ties them all together.

How do you think a liminal community be represented without falling into aesthetic cliches?

The creative process behind Hythloday focuses on the representation of this community through their beliefs rather than their real dimension. In the series, the scenario built up, lacking evidence of location or time. I took advantage of this, and used it as a medium to explore the community’s various state of mind, which is what I felt defined them as “subject matter”. To explore this new landscape, I focused on the seaman character from Thomas More’s Utopia, Raphael Hythloday. Utopia was a fictional story which portrayed the flaws of More’s governmental system through the depiction of an ideal organization located on a non-existent island. For my project, Raphael Hythloday became an inspiration to explore constructed landscapes, where fiction represents a possible future and thus, poses as a challenge to the so-called image of resistant communities.

Why do you think creative approaches are so effective when confronting serious subject matters- whether they be cultural or political?

A creative process allows both artists and observers to tackle projects from a conceptual point of view. This adds new layers of information and constructs a space for a broader sense of reflection. For instance, Hythloday stems from the fight of this community but raises other threads of concern, like the generation and consumption of news, truth and deception, and the privileging of certain opinions versus relating to personal experiences.

Photography especially seems to evoke empathetic engagement, what do you think it is about visual references which encourage mutual understanding and empathy? It seems that people need to actually see what others are going through to feel compassion.

In my opinion, pictures that encourage empathy and mutual understanding are usually related to what we perceive as familiar or weak. By this I mean that It comes from our inner experiences, but also from the enforced narratives within history. As a photographer, being aware of this will transform your photography. By reverting images that might traditionally confirm certain subjects as victims, and picturing them in a way which is closer to what they want to achieve–rather than what our blind, assuming eye might perceive– is the first step towards visualizing different realities.

How have you conceptualized a better world? I know there's no definitive answer for this one, but what do you think a better world might look like? How would you want society to move forward?

This project does not attempt to define in any way what a better world is. The community’s perception on fracking reveals the flaws of the system and many of the characteristics of a dystopian society. Their fight represents the resistance to the advance of environmental destruction and ways of life linked to this. My personal take on the idea of a better world shifts along as I face different situations and realities. To me, a better world should be based strongly on respect and mutual understanding. I believe that we have given up part of our freedom by neglecting certain responsibilities. A better future would mean a greater control through our actions, finding ways of depending less on systematic dynamics of power.

These photos are from a series exploring the de-industrialization of American manufacturing towns and cities. The project started with my interest in photographing the intersection of nature and infrastructure.

As the project changed and grew, I became more focused on documenting small and large cities that, at one point or another, had been major industrial and manufacturing centers in America. Many of the buildings photographed are abandoned, condemned, or in the process of being demolished.

Some of these larger industrial cities have over the years seen government aid and intervention in the hope of revitalizing the local economy. However, many of the smaller cities and towns have been left on their own.

I see this project as an opportunity to document the unfortunate effects of America moving away from being a nation of producers to that of consumers.

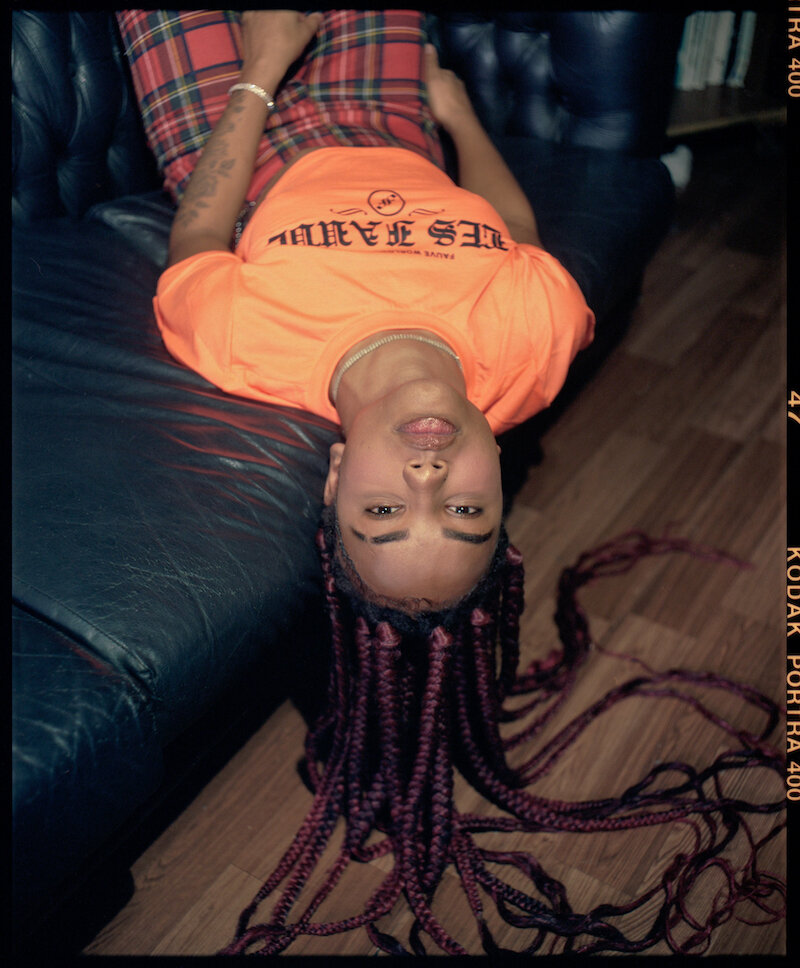

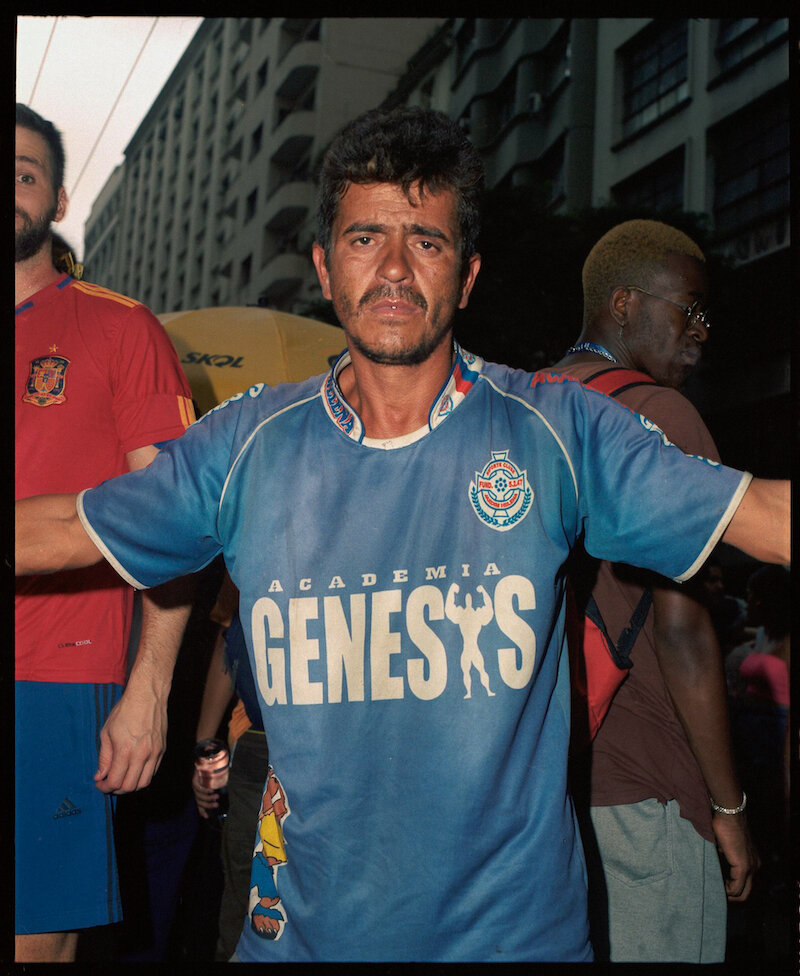

This project showcases various subjects from my travels to São Paulo–friends and models to people on the streets, artists and music producers. The aim of my series is to tell the story of São Paulo (Paulista) culture, a Brazilian street subculture that can only be described in a plethora of images. It's a space where the lines between gender and sexuality are very much blurred and for a couple of days during Carnival, the whole city turns into a giant middle finger towards the Brazilian fascist government. São Paulo offers great cityscape backdrops with pastel tones and brutalist buildings. The people are friendly and proud, with absurdly great style - I hoped to have captured and showcased this culture as genuinely as possible.

I reached out to my dear friend, Romy Ortega, who manages numerous electronic music artists in São Paulo and also serves as my unofficial guide to the streets of the city. We decided to collaborate on telling the Carnival story through the eyes of Paulista’s. I stayed with her and her family and was warmly welcomed to the Ortega family and their many dogs. Navigating the Streets of São Paulo during carnival is hard, especial trying to squeeze through crowds at “Bloco’s” or travelling street parties, with my camera gear. The other challenge was that it was pouring tropical rain every afternoon over the giant crowds of people. Romy also served as a subject and muse during my stays with her, her family and her friends.

I met Paolla di Monica and Clara, her roommate, 2 hours before Paula's flight to Paris for fashion week. She is a model from São Paulo and agreed to have me shoot a few photos before her flight. She has amazing tattoos, beautiful orange hair and great Gucci-esque style. I ended up connecting with Clara and she managed to arrange for us to shoot with local music producer Diamante (easily recognised by his style, attitude and tattoos), with his wife Kerolyn, muse Merry Jenny and baby Shine. Clara styled them in her very own Fauve label, a São Paulo based streetwear brand of which she is the main creator and designer.

The 'São Paulo Fashion Book' is an ongoing photography project and is shot on film exclusively.

Team Credits:

I would like to credit Romy Ortega for putting me in touch with my subjects and showing me around the city. She is my unofficial guide to Sao Paulo (@romyzeta). The editorial with music producer and artist Diamante (@diamante), his wife Kerolyn (@kerolyngeho), muse Jenny (@m4ryjenny) and baby Shine was styled by Clara Pasqualini (@clarapasqualini), owner and designer of Fauve (@fauvebrand). Special thanks to Bernardo Ferraz (bernardoferazzz) Paolla Di Monica (@paolladimonica) Dj Zago (@zagoreal) Thays Vita (@thaysvita_) Thay Rodrigues (thayrodrigs) Livia Ortega (@liviaortega) Karen (Ka_karecos) and all others that allowed me to document their Carnival experience in 2020.

This series is called "Cultivate, Thrive, Wane." Our planet is plagued by flooding, prolonged droughts, and other climate related drawbacks related to global warming. America is particularly implicit in perpetuating the myth that humans aren't contributing to the crisis.

Many parts of the American southwest are now unprotected from oil and mining companies who have begun to capitalize on the newly unrestricted national resources of our Native American tribal lands.

Java, Indonesia is plagued by deforestation and marine pollution. The exploitation of natural resources in Chile are contributing to the extinction of more than a dozen species of animals. These are some of the places I've photographed for this series but they are not unique in their desecration. Earth is facing a barrage of irreversible attacks from all corners.

ag·o·ra·pho·bi·a

/ˌaɡərəˈfōbēə/

noun

an anxiety disorder which involves an intense fear of being in open, often public, places or situations where it may be hard to escape, or where help may not be available.

Agoraphobia is a long-term art project on the relationship between subjects and spaces. In particular, I have been following the life of my grandmother, aged 95, and her confinement within her flat, as she hasn’t left this space for over a decade due to past traumatic experiences. I tried to capture the daily rituals of a domestic life that is mostly marked by stillness and silence. The more I dug into the representation of my grandmother’s agoraphobia, the more a strange sense of claustrophobia emerged within me in the solitude of her apartment. And yet, although my grandmother’s condition makes her life challenging, lacking human contact, I couldn’t help but notice how her inner world has become filled with fascinating details marked by subtle daily domestic rituals and great care for her space. The domestic space becomes both a home-temple as well as home-prison from which she cannot escape. Although this project started a few years ago, I can’t help but think of how current it has become in the last few weeks, where most of us find ourselves in some form of physical confinement due to the Covid-19 lockdowns. The unique life of my grandmother suddenly becomes strangely familiar to each one of us; and my work, that intended to capture the strange condition of the isolation of a single human, is now strangely contemporary and representative of the human condition.

A trópos is a recurring element. A trópos is a motif in narrative. (Yes, also in visual narrative). A trópos is a cliché. Everything can become a trópos, but each of them is not present as itself. It is there to direct to something else. A trópos keeps changing: that's what makes it always the same.

Tropographics is a project by Filippo Bardazzi and Laura Chiaroni—SooS Chronicles. It is definitely not a series of beautiful pictures found by chance on the web. And it isn't either a collection of random weird scenes. This is instead our trip through landscape and photography, in search of tropes around the world. The archive will be constantly updated and expanded with new categories.

All images have been taken using Google Street View.

Bus stops are small reproductions of our lives. You stand or sit there waiting for a ride that can bring you to your final destination. During this wait you share a limited space with unknown people. Sometimes you talk to others, sometimes you just ignore them because you are busy thinking or because you just want to scroll through your phone with no particular reason. We have two friends that we've always known as a couple. They first met at a bus stop 15 years ago. They are now married with children. Life is often unpredictable.

Coca-Cola is likely the only thing you can order in any place of the world you happen to be. In the middle of the desert or in the jungle, on the snowy mountains or on a hammock in front of the Caribbean Sea, a can of Coke is always available, with the same taste, the same packaging, the same bubbles. First sold in pharmacies, now you can find it anywhere except (maybe) pharmacies. Its distribution is so widespread thanks to an extensive advertising coverage, showing the world famous red and white logo. Even Santa Claus loved this soft drink so much that he started wearing these colours as an uniform for his job.

It is said that a dog is a man's best friend. Yeah, maybe. We don't have enough evidence for that. Surely they are everywhere and they populate cities and outskirts together with us for centuries. Most of human activities can be done with a dog on our side. Dogs sometimes act in ways that look mysterious to us: we don't know what they say when they bark or growl in the streets and it's funny how they get in touch by sniffing each other's butts. They are faithful but there is no way you can eradicate their freedom to sleep on a dusty roadside and their will to run behind a passing car.

With Mother’s day fast approaching this Sunday, we’re starting off this week by celebrating Ruby Steele’s “Women on Sofas”. Ruby’s series challenges the Western traditions of domesticity and womanhood, exemplifying how “woman” and “the domestic” are not mutually exclusive terms designed to limit one another. Rather, the women in our lives are not only mothers, but are–”daughters, friends, strangers, writers, artists, models, priests, students, business women, entrepreneurs, musicians, actors, doctors, scientists, technicians”– and anything they choose to be.

- Alexa Fahlman

The domestic space is one we all understand. A home, no matter which way you view the word, involves spaces of conversation, activity and thought. Such spaces hold the potential for negativity and positivity. It is interesting to observe how a space holds itself for someone, and their emotional response to it. Feminist critique considers the human geography of space, both in the gendered nature of space and existing conceptualisations of space. A magnitude of diverse environments within our society differ in their pre- existing tendencies to welcome one gender or the other. Culturally, we are encouraged to adhere to this. “Women on Sofas” was driven by a curiosity about the space a woman occupies in contemporary western society. The work explores how we experience ourselves in the domestic and public arenas, whilst celebrating our diversity and power in unexpected ways. It looks at the pride and pleasure we take in our strength and resilience, and in challenging society’s expectations of us. In spite of growing freedoms in many areas of society over the past century, the domestic sphere is still often seen as women’s terrain. It is a space into which we are welcomed. It has been interesting to observe this space, disrupt it and take it beyond its ‘natural’ limits, whilst exploring our emotional response to it. The women come from diverse backgrounds and cultures which span eight decades. They are mothers, daughters, friends, strangers, writers, artists, models, priests, students, business women, entrepreneurs, musicians, actors, doctors, scientists and technicians. Women on Sofas was the project that offered me the opportunity to celebrate these women, both ones I knew and ones I was yet to meet. The sofa is more than a domestic object; it is imbued with symbolism and a rich history. It holds a familiarity and is an invitation for togetherness. These photographs bring that intimate space into the outside world and ask us to reconsider what it means to get comfortable, and feel safe. They also consider the social function of the sofa, and allow that function to broaden into the idea of bodily experience. The image of the sofa initially suggests inactivity. “Women on Sofas” works to challenge that. “Women on Sofas” says ‘I am in the world, I’ve made a surprising home here, and now I’d like to welcome you in.’

All the images in this work derive from wallpapers and screenshots taken by different users while playing Grand Theft Auto V —a video game set in Los Santos, an “open world” scenario that closely resemble Los Angels and its surroundings. Thus, the city of the Studios, of Hollywood and film industry, becomes itself a staged set and a virtual replica, a duplicate of its original. This fake city, this double, may bring to mind Buthrotum, the citadel built by Troy’s exiles in the likeness of their destroyed hometown. And just like Buthrotum, Los Santos looks more like a remembrance than a copy. It is immediately familiar and recognizable, but at the same time vaguely odd and ambiguous. Pieces are missing, distances are altered, dimensions changed.

Here, somehow and surprisingly, what Vittorio Sermonti wrote overall about the Aeneid is valid as well: “We must adopt the syntax of dreams, which absorbs [narrative] inconsistencies in a clear realism, meticulous, conflicting and tangibly unreal.”

Is it possible to photograph such a virtual place? And what does it mean to do so? What light are we writing with? These and many other questions, some of them also concerning the topic of authorship, have been already faced by many artists. Nonetheless it’s a matter of investigation that continues to fascinate.

Finally, this work was meant as well as a tribute to a long series of great photographers who worked in Los Angeles widely throughout the second half of the past century. Even if it is mainly through cinema that the city of L.A. has become part of the collective imagination, however the influence of these artists can not be underestimated. With their own perspective, all of them contributed to create an idea and an image of the city that is still vivid and lasting.

As the weeks of uncertainty progress, I become more and more aware of both the luck and privilege which allow me to sit comfortably at an IKEA desk, and write to you each week. When I walk my dog down a quiet neighbourhood street, I pull my mask from my face to feel the fresh air coat my lungs. Just for a few seconds, a crisp inhale tells me I’m able and alive. Those of us, like myself, who interpret for a living, might feel as though we’ve exhausted our sensory apparatus’ trying desperately to comprehend the state of the world–in fact, we probably have. However, as painful as exhaustion may feel, it reminds me, like breathing, that I’m still alive, and that being able to feel anything at all is something to be grateful for.

Our senses are often one of the things we take for granted the most in life. Here, Alena Shilonosova takes us through Rusinovo, a street of the blind and visually impaired in the town of Ermolino, Kaluga, Russia. Her work explores a community of those regarded as “invalid”, their day to day lives, and their hardships.

- Alexa Fahlman

Until 1995, Rusinovo was a separate village where the visually impaired were sent from different regions of the Soviet Union. In 1948, the basic enterprise for the blind and visually impaired was built here. The main activity of those in the village was the installation of boards for TVs called "Rubin". After the political rearrangement, the development of the village stopped and the construction of new houses and a rehabilitation centre were frozen. The village was attached to the town called Ermolino, and became what is now a separate street situated five km away from the city, where people without visual impairment also live. Nowadays, the blind spend their time in a workshop, manufacturing “RUSiNovoPak", a collection of medical pipettes. However, it’s considered unprofitable for the enterprise, therefore in the neighbouring workshop, people without disabilities produce cardboard to help cover the losses of the workshop for the blind. Since the Soviet times, there has been an assembly hall in the production building, where the choir of the blind, a library and a gym have organized for many years. The blind and visually impaired live in several five-storey houses; there are private houses behind them on the street and it looks as if it were a street in the usual village.The residents know very well where everything is situated. They are able to get to the shops, to the production building and to the post. If it is needed, neighbouring people will help without hesitation. The larger half of the blind in Rusinovo are seniors who moved here during the Soviet period; children who were born with a full vision have left. In total there are 115 blind and visually impaired people in Rusinovo.

Alexander Rakovich works as Chairman of the society of the blind in Borovsky district. He lost his vision at the age of five because of flu complications. He works in Rusinovo and lives in the neighbouring town of Balabanovo, where he also runs the business.

The evening meeting in the library devoted to A. I. Solzhenitsyn.

In 1942, the house of Victor Sergeyevich Solovyov in Prudischi village in Kaluga region was bombed by an airplane: Victor’s entire family was injured by the glass. Victor received an invitation from the Society of the blind and moved to Rusinovo in 1954. After the incident, he had residual vision, but eventually lost it completely.

Alexander removes the toys from the Christmas tree after the New Year holidays.

The production building has a daily standard of 2400 pipettes per shift. Employees say that there is almost no work that should be done. Someone finishes the daily standard before the work shift is over and leaves early. Moreover, the work week is shorter than most - people work just 4 days per week.

Natalia Vyacheslavovna Belopuhova was born in Rusinovo and lives there till now. Vision problems were inherited from her blind parents.

The first and the last steps of the stairs are marked in yellow color for visually impaired.

Sergey Valentinovich Ivanov has been blind since he was born. It was inherited from his visually impaired father. When someone asks Sergey if he wants to be sighted, he answers, “How is it possible to want something that I don’t know?”

Daily routine helps the residents navigate. Many can easily find the right way through Rusinovo just by using touch.

The residents go to the libraries to read books in Braille and listen to audiobooks on flash drives. Sometimes there are literary evenings: a librarian invites a lecturer from Borovsk, which is situated close by, to read the biographies of writers and their works aloud.

Ivan Sergeyevich Hripunov moved to Rusinovo with his family when he was 40 years old. At that time, his vision was gradually lost.

Table tennis for the visually impaired called “Showdown” reminds me of air hockey, where people are guided only by hearing and touch. The blindfold makes the game equal between the participants with residual vision and the blind.

A guide made of rubber tracks serve to and from the production building. They lead from the first floor of the building to the workshop on the third floor.

Agadzhan Kakadzhanovich Khanov or just Alek, as the locals call him. He has lived in Rusinovo since he was 23. He lost his vision after an accident.

Residents from Rusinovo do not go outside on their own. Their children and relatives help. They have a habit of going to a few shops where the shop assistants help them without cheating, they don’t go to a self-service supermarket alone. They go there very rarely and only with the relatives.

On the opposite side of the production for the blind there are greenhouses where flowers are grown. Only people without disabilities work there.

After the collapse of Christianity, with its inherent belief in the afterlife, the visible space became the only possible place for humanity to live, in the future. The aspiration to learn the outer space replaced religion, instead of the belief in the otherworldly came the belief in progress. Achievements in space exploration were officially presented as part of the advance towards a communist society, as well as the triumph of science over religion and, in a way, desacralization of heaven.

With the evolution of astronautics, a new mythology of space was formed. It was based on the simplified theory of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky about space colonization. Soviet propaganda was responsible for the creation of mythological images in the state. The first symbols were Belka and Strelka, after them — Yuri Gagarin, the first human to journey in outer space, endowed with a lot of positive qualities and completely devoid of negative ones, which immediately made him a hero and an immortal symbol. All stages of the Soviet space industry were represented in literature, cinema, architecture, and even in the household items design.

The picture of reality of a Soviet man was built in many respects around the myth of space exploration. The created images allowed people to feel involved in what was happening and to be proud of the state. The myth was working for the Soviet ideology, but as the USSR collapsed, ideology changed. Reality began to transform, as well as its relation to the myth. The cosmic myth continues to exist, but does it now affect reality?

Collective memories of the first manned flight into space construct national identity and unite different age groups. Leadership in space gives a sense of national pride, which derives from the Soviet era and is still strong both among the eyewitnesses of that event and their descendants. Cosmic mythology became one of the bases of national and group identity.

On a formal level, I am very conscious of the compositional armature on which the content rests. I believe the most successful images embrace the two-dimensional space of the photograph, and certain formal techniques help make that possible. It makes sense why I was always drawn to the 8x10 camera (although now I'm also using a Phase One IQ4 with a tech camera). Sometimes my images belong in a series of images with a strong conceptual motivation, while others are almost entirely formal experiments that serve as a pause or a beat in a more heavily freighted series of images. Usually the symbolism of my images is subtle, with their formal concerns often taking a front seat. Lately though, my work has taken a more explicitly topical turn.

Last fall, deeply troubled by the state of our country and its future, I decided I needed to channel my anxieties and turn my lens on an America in crisis and make a body of work that was more explicitly topical than what I had done previously. Of course, there is a long tradition of such endeavours throughout the history of photography in America. Many of the most notable works in the first half of last century were lauded for a new objectivity, but this objectivity was the product of privilege. Consideration of the conditions that allowed for this “objectivity” were conspicuously absent from the content. I hope I can approach this project in such a way that allows for my privileged subjectivity to be interrogated in the analysis.

While our divisions are more starkly apparent in the age of Trump (exemplified today in so many ways, and certainly to be made more so in a post-COVID environment), the reality is that America has been manifesting, exploiting, and even weaponizing divisions since its founding. The grand American narrative and its illusions are at odds with the lived experience of most Americans, and symbolic and literal marks of that contradiction are rendered throughout our landscape.

A subtle look at contemporary Hong Kong, Gideon de Kock’s “Short Stories” is an ongoing project now encompassing almost 5 years worth of street and documentary film photography. He writes to me stuck from his family home in Somerset West, South Africa. What was meant to be a short family visit with his girlfriend, subsequently turned into a 4-week lock-down and self-isolation period, where he now waits until further notice to return to Hong Kong.

- Alexa Fahlman

My personal depiction and documentation of Hong Kong started around the time I picked up my first camera as an adult. I had just moved to the city after 18 months in Mainland China - the "small" city of Taizhou to be specific - in the capacity of an English teacher. As a musician prior to all of this, I was unable to pursue this passion due to unfamiliarity with the new environment, moving around, and lack of an "in" into the musical community, if you will.

I like to walk, as a result I like to explore, and out of the need for a creative outlet came photography - a comfortable addition to an already solitary and somewhat insular habit. Hong Kong is such a visually stimulating city I couldn't help but find things to photograph. I feel many parts of Hong Kong are unrepresented to an outsider, or expat like myself, and so I took it upon myself to document. In hindsight, I was simply looking for answers to unknown questions at an uncertain point in my life, and the depiction of an underrepresented Hong Kong and an invisible working-class demographic became a vessel for this. Inevitably, it became an ongoing project themed around empathy; empathy for others and your environment - the place you currently call home. I was never interested in capturing "grand gestures"– moments of awe and wonder–as I've always been enamored by the beauty of subtlety.

As in many cities like Hong Kong the pace of living and work can be taxing on the individual, and it becomes too easy to be sucked into an environment and routine where we look outward for sustenance, beauty and pleasure; our blinkers tightly secured against the mundanity of the constant. Some don't see their homes any more, they don't truly *see* their neighbors. This documentation eventually formed the foundation of my first solo photo book Some Near Some Far.

These images are here to remind us of what we’re missing when we lack attention; moments of the surreal, moments of humour, moments of beauty–all grandiose in their near invisibility–lost were we to not pay a modicum of attention. Hong Kong has had a turbulent time since the Umbrella Revolution back in 2014, to the ongoing Extradition protests in 2019, and now we’re all sharing the burden of the current COVID-19 pandemic.

These “short stories” lack context because they’re rich enough for you to craft your own narrative. They’re here to encourage empathy for your fellow people and place, to develop a deeper understanding that we’re all sharing so much, but these photos are also filled with nuance that requires understanding and patience to wholly grasp. On the most surface of levels, these are really just beautiful vignettes of a vibrant and dynamic city, captured on 35mm film.

"Fiction" is a project that I have been doing since 2016. By observing spaces with a mixture of real and unreal factors that people construct in the daily environment. This project explores people's various desires behind this behaviour model, as well as unveiling the challenges they are facing towards ideology and traditional values.”

edited by Alexa Fahlman

Educational centres dedicated to their regional districts are a unique feature of Russian life, carrying a centuries-old history. While educational centres started to become popularized in 1905, many of these remained private centres primarily serving affluent families. However, as response to the pedagogical changes that were taking place in post-revolutionary Russia, the calls for universal access to these educational centres were granted. In turn, these educational centres were organized by regional and local authorities, and became a common institution. Within urban areas, working families especially benefitted from these centres as they provided both education and a form of childcare.

The teachers and students enjoyed great variability in the formats and educational approaches; arts, crafts, writing, sport, etc. Activities were organized in local surroundings, while lessons were delivered in school rooms and pioneer clubs within property management agencies, trade union committees and factories. In an effort to support these centres, a 3% tax was charged to those living in the community as a means to contribute to the centres’ upkeep. Between the 1970s and ‘80s, the centres flourished due to adequate funding, equipment and experienced teachers. Yet, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, many centres were faced with unprecedented challenges. Departmental support ceased, and funding was drastically cut. The number of these centres significantly decreased, many of which were bought and sold as real estate.

Nowadays, these district centres carry on their work as supplementary educational centres. While some were able to implement newer systems and integrate into commercial services, others have tried to keep what they have. They remain housed in the basements and semi-basement floors of buildings, and are forced to survive using their own resources. Despite these difficulties, the educators continue to work, and their purpose remains the same. Children are enrolled in classes for free, and those involved in the centres have begun to see a new generation attending these classes, most of whom are children without any other opportunities.

Parallax is a series of images made while traveling the eastern half of America working as a camera operator for an aerial survey company. Spending up to ten hours hours flying a day, one experiences a shifting of perspective. In flight, the landscape quickly becomes an object shifting into division - seen from the ground in layers and detail, then from above, as flat and broad. We never see the images or how they're used, but we're told that the images' quality is so high that one pixel is equivalent to two centimeters on the ground. Printed at full quality, the image could cover the entire area photographed. The image is more real than we can fully comprehend. In addition to this directional shift in perspective is also a location shift as we land in small airports across the eastern half of the US. The rural, urban, and suburban areas start blend together, further confusing the subject-object relation as the familiarity with a town without context (sometimes forgetting what state you're in) seemingly floats in a void. This division, rather than creating a synthesis, or a more complete view of the world, further complicates it. Communicating our lack of ability to fully grasp the Real.

In 2012, photographer Sayuri Ichida began her path to New York. Following a similar path was Japanese ballet dancer, Mayu Oguri. They met in 2017, and formed a friendship out of a shared struggle to settle in a foreign country–the overwhelm of self-doubt, alienation, depression, and lingering regret. These experiences of displacement became the impetus for their ongoing photographic collaboration Stranger in a Strange Land. As the series sees Mayu perform ballet movements in unorthodox locations, Sayuri captures the ebb and flow of an immigrant’s search for belonging in a foreign country.

- Alexa Fahlman

Mayu is a Japanese ballet dancer who currently works for the New York Theatre Ballet. We are both immigrants from Japan, and our paths to New York were similar, with both of us spending a few years in Europe before coming and settling in the city on our own. On our journeys to New York we both experienced various degrees of self-doubt, alienation, depression and at times regret, ultimately followed by a sense of reawakening and rediscovery of our inner selves. With this series I aim to convey some part of the jarring experiences we independently shared as immigrants looking for their place in a foreign country.

Can you speak more about your path to New York as a Japanese immigrant? What made you want to settle in New York? Do you miss Japan?

Before I left Japan, I was into the fashion industry and I always had this impression that Japanese fashion was influenced by western trends. At that time I was working at a commercial photography studio and tired of seeing these copied ideas and creations. I made up my mind and decided to move to a place where the trends are born. I first spent two years in London where I first got a taste of life as an immigrant. In 2012, due to a visa issue I had to leave the UK and set the next destination to New York. After spending a few years far from my home country, I gradually started rediscovering the beauty of my own culture.

As time has passed, how does your experience compare to what you expected?

Every goal I aimed for took much longer than I anticipated, but I feel that part of the experience and the setbacks we experience as immigrants are necessary to move us forward.

In retrospect, what was the hardest part about immigrating to America? Would you have done anything differently? Do you have any advice for those wanting to follow a similar journey?

Dealing with the feeling of being an outsider was the hardest part for me as an immigrant rather than technical issues such as language barrier or visa issues. If I could have done something differently, I would say that is to go to a university in a foreign country rather than just going to a language school or go straight to start living in the country. I was young and didn’t think realistically back then, but putting yourself in a situation where you have no choice but to communicate with other people and use their own language and idioms is essential to understanding the culture.

How does the political tension and anti-immigrant rhetoric in America affect you personally–your work, and your art?

I try to ignore politics in general, but the anti-immigrant rhetoric offends me to my core.

Dancers usually perform on stage, but because I shot Mayu on locations that could be considered unorthodox for a dancer, the combination of a ballerina and outdoor scenery gives the series a sense of dissonance. To emphasize this effect I knew that I had to do things differently from a typical dancer’s portrait so I also deliberately set out to shoot her as an object in a frame. I kept asking her to express something different from beautiful formal ballet dance. Everything she does as a dancer is so beautiful, so I asked her not to be too beautiful.

Mayu’s pregnancy with her first child in 2019 was a beautiful occasion for both of us to rethink the meaning behind this series. We decided to continue in the same style, shooting on location throughout the city. I personally find the the lines of Mayu’s body against the bare colorful backgrounds of city walls astonishing. To me they represent the beauty and grace of becoming a mother, as well as the strength that is expected from a woman to be one. I see these pictures as a reminder that our future should always take priority over our past.

“In 2015 I spent A Month in the West and found there what really interested me in photography. The large spaces, the horizontal structures, the colors, the light, the desert, the mountain, the lost places. In 2019, I went back there. It was a way to follow up on this work, but by bicycle this time, just to see the difference. Over time, cycling has become more than just a means of transport. Being on the road riding a bicycle stimulates the imagination and as a photographer leads to a different narrative.”

“The European part of Russia was originally populated mostly by Finno-Ugric people, not by Russians. There are still four million of them. They speak different languages, but united not only by blood. They are pagans — sometimes, having converted to Christianity or Islam, without fully realising it.

Many of our customs and tales came from these people. And our roots as well. I found out that some of my grandparents were partly Finno-Ugric, though they never spoke about it, for political reasons. Their history is similar to the indigenous people of North America – the Finno-Ugric lands were, in fact, colonized by Russians and Tatars. History is always written by the winners and that’s why our origins are seldom talked about – though it’s no secret. The locals are skeptical of the federal authorities as well. No wonder why: i.e., just look at the terrible life conditions in many villages. So, these people rarely talk to strangers.”

“They are also quiet about their pagan tradition because there’s a dark side to it. A story from an Udmurt village: the village chief took apart the prayer house and rafted the logs down the river. A few days later, a fanatic cut off his head. And those stories are aplenty.

From the Baltic Sea to Western Siberia, Russia remains Finno-Ugric land, in a manner. If you only go a couple of hundred miles eastward of Moscow or St.-Petersburg, you will see the Finno-Ugric matrix through the depressing provincial routine. In some remote places, tens of thousands of real pagans live. This phenomenon in the supposedly Orthodox Russia is a silent agreement of the people with their rulers.”

“I travelled to many places where Finno-Ugric people live: Udmurtia, Mari El, Chuvashia, the east of Leningrad region. I saw their world full of archaic things, with Nature as the main religion. But the tradition may soon be gone due to globalization and “Russification”. With my project, I want to save some essence of this original wild beauty.”